Evolution of the ‘Third Place’ in a Hybrid World

By Chelsea Perino

This article explores what ‘hybrid working’ means for the role of those workplaces often referred to as ‘3rd Places’ – not the employer’s official office or the employee’s home.

I’ve just collected my double caramel latte from the barista and settled myself at one of the shared tables, seating now separated by transparent plastic partitions, a response to increased social distancing regulations. I open my laptop, plug into the outlet specifically designated for my seat, sign into free Wi-Fi, and take a brief pause to assess my surroundings; next to me there’s a guy also on a laptop, seemingly both engrossed in whatever he is doing and yet quite oblivious to the animated conversation taking place behind him. At the breakfast bar looking onto the street one man is reading the local newspaper, while another is scanning his iPad. In the back corner a girl looking to be in her mid-twenties, wearing what I imagine to be a noise cancelling headset, is engaged in a video conference call.

Remote work is not a new concept. Even before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic there were estimates that 10% of the workforce consisted of remote workers (1). However, COVID-19 has instigated the largest ‘work from home experiment’ of all time, driven by organisations closing their offices to all but non-essential staff.

Remote work has been around longer than many realise. While not mainstream, as early as the 1970s there are examples of people working outside of the traditional office. Large and unplanned

fuel price increases motivated some workers to transition away from the ‘co-located’ (i.e., traditional) model to a more flexible workday; the abandonment of the 9-5 office day enabled people to work elsewhere, be it from their homes, coworking spaces, or what we now called ‘third spaces’ (2).

This kind of remote working is a very different from the café scene I recounted above, and both are unlike what existed even 15 years ago. At that time, in 2006, I remember leaving on a trip around the World after graduating from university. In each new city priority number one was locating the local internet café or expensive café that offered Wi-Fi internet access with a purchase.

Pre-pandemic, the digital nomad life was almost idolised; visions of young carefree people working on remote beaches, without a schedule or a care in the world was exaggerated by social media and the rise of influencers. So, when COVID-19 drove mass populations out of their traditional workspaces and back to their homes, the initial sentiment was one of excitement. It’s seemed almost akin to a high school graduate headed off to university and for the first time experiencing the freedom that comes from self-management – no more parents looking over your shoulder, enforcing curfews and dinner times. More autonomy. More responsibility.

However, as the pandemic progressed, and returning to the office was nowhere in sight, the sentiment quickly began to shift as the challenges of working from home became more apparent.

A study by digital transformation leaders, Adaptavist (3) found that focusing on work, followed closely by coping with the mental stress of the pandemic and overall market uncertainty marked some of the greatest challenges faced by professionals trying to navigate the new work from home environment. In addition, the pressure from being ‘always on’ was observed to have a negative effect on motivation and increased incident of ‘burnout’.

Figure 1 – Work From Home’s Greatest Challenges

Similarly, (Business) Insider, an online news site, listed issues with technology, and avoiding domestic distractions, as challenges to productivity (4), while Willis Towers Watson’s 2021 ‘Emerging from the pandemic’ survey showed that “employees working from home are nearly twice as likely to say they feel disconnected as those working onsite” (5).

(re-) Evolution of Workplace Culture

At this point, I am aware that this might not be painting a positive picture for the future of work. Lowered productivity, an increase in stress, and sense of isolation are absolutely issues that need to be addressed. With such concerns, it is easy to miss that we are witnessing a (re)-evolution (that means both revolution and evolution) of workplace culture. On the one hand both employers and employees are becoming increasingly aware that ‘work’ is as much a state of mind as it is an output and on the other hand, the choices of physical locations where work can be carried out (in policy and physical terms) have increased significantly.

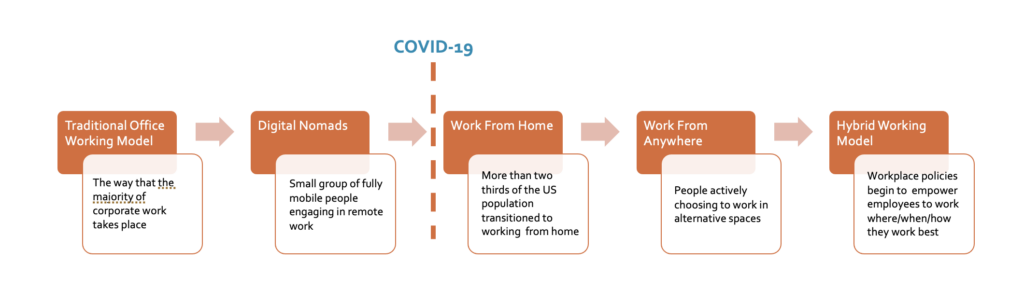

To understand where we are headed, we need to take a step back and look at where we have come from. The below flowchart represents the progression of workplace definitions. Pre-pandemic workers fit into two general categories – if you worked in an office then you were considered a traditional office worker, and if you didn’t you fell into the ‘digital nomad’ category. (Don’t get this confused with the evolution of workspace, which has a very different timeline and is much more mature) (6).

Figure 2 – Workplace Evolution Pre and Post COVID-19 (Source: Chelsea Perino)

A change in mindset about ‘work’

The restrictions brought about by COVID-19 altered geographically where we work and thus also how, when and through which channels we do work related activities. Perhaps more impactful for the long-term, these changes radically altered the way previously office-based workers thought about ‘work’ as an activity. Furthermore, the phenomenal thing about this change in thinking was the rate at which it took place and the consequence for traditional models of workplace provisioning. This change in thinking directly informs the current conversation: the role of the office in a world where many people are measurably more productive for certain activities in places other than the office.

One could argue that pre-COVID-19 ‘work mindset’ (as opposed to how you act outside of work) was almost an afterthought because there were distinguishing markers that indicated when you were expected to work and when you were not. For example, if you were in the office then you were expected to be doing work-related tasks. When you took your lunch break, even if you still ate in your offices’ cafeteria, you moved out of the work mindset and into one that was more socially orientated. Then, at the literal end of the day, you switched off your computer and went home and mentally ‘turned-off’ until you returned to work the next morning.

The ‘always on’ mentality, a mindset that has arisen because of globalisation and technological accessibility, has brought the tension between ‘work’ and ‘life’ to the forefront, and has ironically been a catalyst for a renewed focus on work-life balance. Some would even argue that it’s unintentionally become a champion for more flexible work methodologies. Because people feel that they are working ‘all the time’, they now make a conscious effort to separate their working hours from the rest of their lives. COVID-19, however, made that increasingly difficult as suddenly the physical difference between work and non-work environments (i.e., the office versus home) was removed.

In 2021 the Harvard Business Review (HBR) conducted 200 in-depth interviews with law and accounting professionals, both men and women, between ages 30-50 years old, about their efforts to achieve work-life balance. While findings showed that many of the interviewees described their jobs as “highly demanding, exhausting, and chaotic” and in the majority accepted long working hours as an integral part of their work; interviewees were then asked about the strategies they used to consciously maintain work-life balance.

The HBR concluded that ‘achieving better balance between professional and personal priorities boils down to a combination of reflexivity— or questioning of assumptions to increase self-awareness — and intentional role redefinition’ (7). Both insights have a direct correlation with decisions about where, how, and when a person works best, and how others perceive those decisions; a decision that is influenced by a combination of the physical location characteristics and the mental state of the individual, and a conscious and constant detachment and reattachment between work and non-work mentalities and locations.

The first phase in this mindset progression was ironically a physical transition: from the office to primarily working from home. No longer was this work style associated with the most progressive of companies; it became an experience had by all, regardless of industry, department, or title.

Inevitably, the initial allure of working from home lost its luster, an issue that organisations were slow to address. It wasn’t that they didn’t try, but the changing levels of COVID-19 threat, which impacted markets at different intensities at different times, combined with a radical new workplace dynamic that everyone was trying to understand, acted to debilitate the organisations’ ability to respond effectively. It became impossible for businesses to disassociate local (usually governmental directed) COVID-19 rules from global workplace policies.

As a result, individuals started to take decisions into their own hands. Banned, for all intents and purposes, from returning to their old office environments, people started making alternative arrangements. Enter the rise of ‘Work From Anywhere’. At this point, the realisation that for many people work can take place in spaces other than between four pre-defined walls, at a desk, from 9-5pm, became evident to both them and to their Employers/Clients.

Employees began organising their own workspaces based upon what provided them with the most optimal personal experience. And employers, for the first time in a lot of instances, embraced that decision. What else were they going to do?

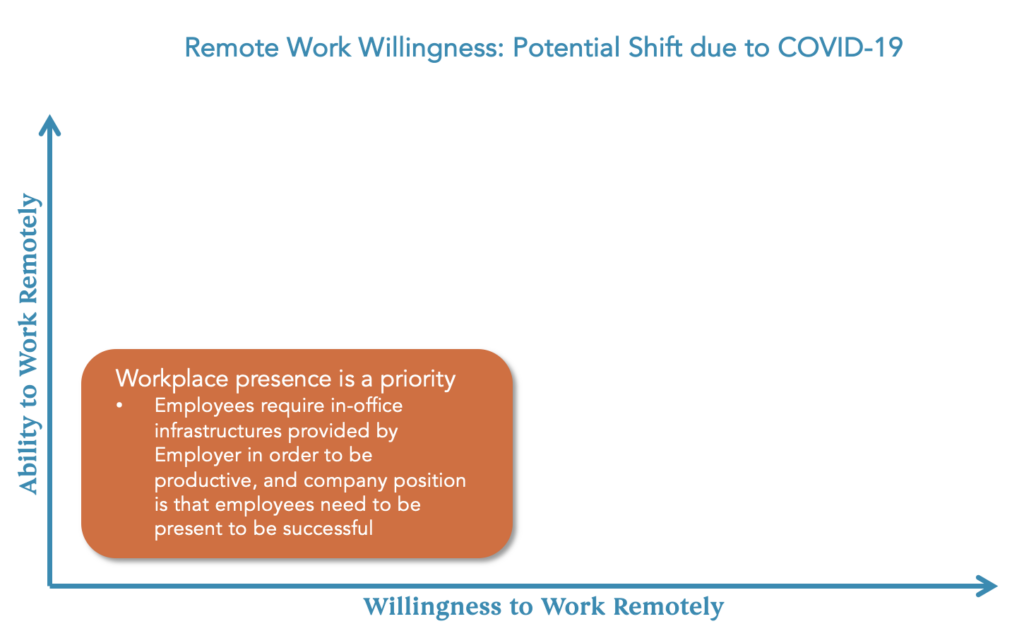

Ability to work remotely versus willingness to do so

The Remote Work/Willingness Matrix below presents an interesting dynamic: organisations and their peoples’ ability versus their willingness to work remotely. Pre-pandemic, workplace presence was usually, in some form, a non-negotiable. There was an inherent perception that office presence equated to high productivity and work than anywhere else. As a result, we see a tension building between an employee’s ability to work remotely, and their willingness to do so based on the perception that productive work could only be achieved in an office environment.

Figure 3 – Remote Work/Willingness Matrix (Source: Chelsea Perino)

A senior executive at a Global PR firm recalled her experience trying to motivate her team to take advantage of company-wide remote work policies. On paper the policy was clear: employees could choose where they wanted to work (from home or elsewhere) on condition that their manager was aware and approved, but even after her clear communication that this was an option, her team refused to do it. “It wasn’t until I actively started working outside of the office and being very vocal about doing so, that slowly people began to try other options” she said.

Of course, not all organisations had flexible/remote working policies pre-pandemic, but COVID-19 acted as a catalyst, thrusting most everyone to embrace remote/home working, willing and able or not. With that adoption, came a rapid shift in the role that organisations play in empowering their employees to work in places that the organisation does not actually control.

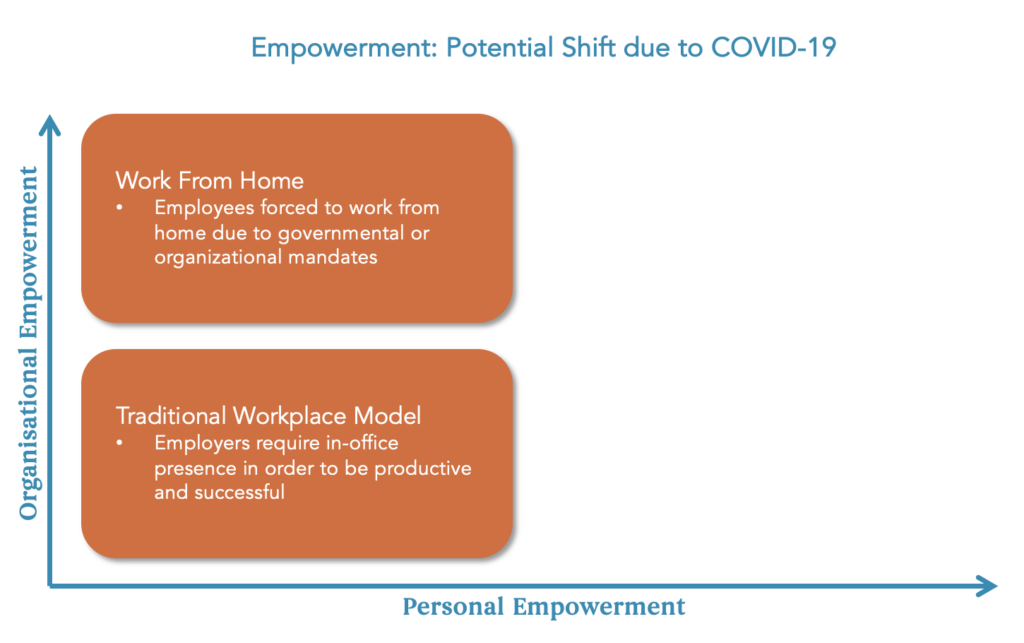

Empowerment

The second matrix we can examine is about Empowerment (see figure 4, below). The left side of the matrix is where we were at the start of the pandemic: the traditional office quickly transitioned to a mandatory WFH scenario, and while many organisations took steps to try and enable a better WFH experience, in many cases employees were left to fend for themselves.

Figure 4 – Empowerment Matrix (Source: Chelsea Perino)

We discussed previously the challenges associated with working from home; as the WFH experiment matured; many solutions emerged to address some of these issues, many of which were infrastructure based (think better Wi-Fi, double screens, ergonomic home office equipment), but the one challenge most difficult to resolve is the feeling of isolation that comes from a fully virtual work situation.

Here’s where things get interesting. What prior to COVID-19 seemed generally to be a black and white model, suddenly gained a lot of gray areas. People who could not access their office but also didn’t want (or were not able) to work from home started to explore alternative options. But this gave rise to a fundamental question, one that has plagued all workplace strategists for years but now is a mainstream concern for both individuals and organisations alike: What constitutes as a workplace?

Third Places defined

In 1982, Ramon Oldenburg and Dennis Brissett described ‘third places’ as public spaces crucial for neighbourhoods as a space to interact, gather, meet, and talk. These places foster a sense of community and provide an opportunity for open exchange of ideas and impromptu social interaction (8).

While their definition focused on third places from a social perspective, within the context of COVID-19 we should think about third places from a work perspective. As people experienced a prolonged non-office working culture, compounded with the challenges of working from home, employees and organisations alike began to consider what role the ‘third workspace’ i.e., not the employer-controlled location or the employee’s home, could play in the larger corporate real estate ecosystem.

COVID-19 created an interesting tension between peoples’ desire to return to work versus the desire to work safely. People could not work from their traditional offices, they didn’t want to work from home anymore, but they also had concerns about the safety of working environments in which they were not in control (i.e., anywhere away from home). Working from less familiar ‘third spaces’ where exposure to ‘unknowns’ are inevitably higher, to many people, felt like an unacceptable level of risk.

So, what happened? People turned to specific kinds of ‘third spaces’ – those that mirrored their own level of caution about protecting against COVID-19. Flexible workspace providers like The Executive Centre surprisingly saw an increase in their coworking revenue during COVID-19. Why? Because people wanted to work in an office environment but access to their organisations’ offices was limited, but they also wanted to be certain that their environment was safe. Flexible providers (many of whom went out of their way to communicate all the safety measures used to ensure the healthiest workplace) seemed like a good solution.

Work from anywhere

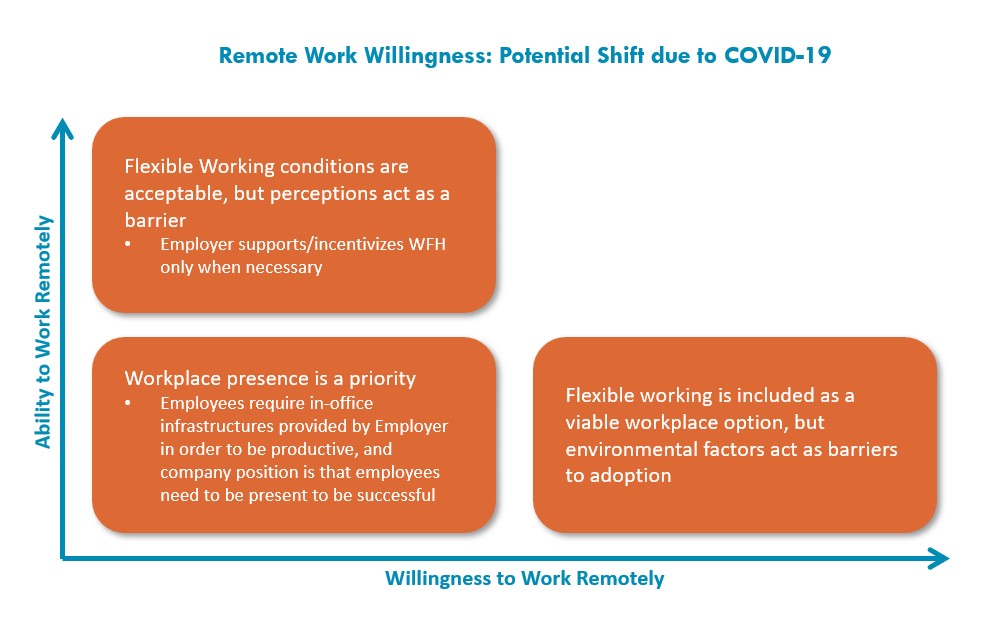

You can find the (figure 2) Work Dynamic flowchart’s ‘Work from Anywhere’ bubble, reflected in the bottom right-hand side of the Empowerment Matrix (figure 5). The ‘Work from Anywhere’ concept arose because of organisations’ lag in providing strategic policy and infrastructural workplace changes, but also people taking control of their workplace decisions and making choices that allowed them to work in an environment where they felt most productive but also safe.

Figure 5 – Empowerment Matrix [Source: Chelsea Perino]

This shift is also reflected in the Remote Work Willingness Matrix (figure 6); in the same position (bottom right). Note that employees are no longer tied to the idea of working from an employer-controlled office. Post COVID-19 the perception barrier has been largely overcome, however the limitations of working from home has motivated people to find alternative solutions that provide the optimal environment.

Figure 6 – Remote Work/Willingness Matrix [Source: Chelsea Perino]

So, what do ‘third spaces’ actually look like, and what are some of the motivations and considerations that we need to consider when identifying the ideal ‘third place’ workspace?

If we return to the chart which outlines the challenges of working from home, we can hypothesize that an ideal workplace would remove those barriers, and have the characteristics as set out in the table below:

| Factors that challenge working remotely (from home?) | Ideal ‘Third Space’ characteristics |

| Focusing on work and not getting distracted by domestic matters | Provides minimal distractions and allows for focused work |

| Switching off (because tempted to keep working as opposed to domestic matters) | Alternative location that creates physical separation between ‘work and non-work life’ |

| Creating a suitable workspace | Comfortable seating, natural light, access to F&B |

| Lack of IT and office support | Reliable infrastructure |

| Managing virtual social lives | More face-to-face interactions (reduces virtual meeting stress). |

| Scheduling work calls around the people that share the home environment | Spaces that allow for virtual collaboration without having to accommodate co-habitees. |

| Coping with the mental stress of a global pandemic and uncertain economy | Opportunity to connect with others that share the same concerns and are facing similar challenges. |

| Need for security related to information or matters discussed | Secure space, free from opportunity for others to breach the privacy of the activity e.g., HR interviews, counselling, dealing with personal data. |

However, there are two things that the data from the above chart does not address. The first is that ideal workspaces are inextricably linked to the kind of work we are doing. The second is that people are inherently different in how and where they perform best. Therefore, it is difficult to develop a generic definition of what exactly constitutes an ideal workspace. However, one thing is certain – it is very personal.

Herein is where the opportunity lies. Now into the third year of the pandemic, we see an evolved work scenario emerging. People are irrevocably conscious of their individual workplace needs and are first asking the question of themselves: where do I work best for the task at hand; and then of their employers: give me the tools, resources, and support I need to do my best work.

No all-purpose ‘perfect place’

There is no right answer to the first question: What makes a workplace the most productive? An ideal workspace might be as casual as a café, or a place more specifically designated for work such as a flexible workspace; it might be a home office or even a comfortable section of your sofa; or it might be a traditional office. The thing that needs to be recognised here is that no work is the same, and that in and of itself should justify multiple workspace types/settings.

Miller Knoll (formerly Herman Miller) have been researching workplace dynamics for decades. In their recent report ‘The Future of Work: Three shifts to help organizations navigate a post-pandemic future’, they suggest three key areas that an office can (and should) support

- Sociality

- Collaboration

- Focused Work

This can be applied to all workplaces, to help us understand how to think about the context of work and the role that alternative spaces play in that experience (9).

If you tried to create a matrix that consisted of a spectrum of individual tasks versus those that require collaboration on one axis, and the type of workplace that suited those tasks best on the other, you’d find yourself in quite a conundrum because there is no one-size-fits-all visual of that relationship. Why? Because the manner in which everyone works best is different. I might prefer to do focused work in a café, where there is action around me but nothing that directly needs my engagement, while another person might find that distracting. Conversely, someone might prefer to have meetings online versus in person. The key factors here are:

- self-awareness of your workplace setting preferences for different types of activity,

- your awareness of and access to a variety of practical workplace options and

- the positive versus negative perceptions of making the choice that works best for you

Hybrid Working Model

While workplace practitioners continue to explore what elements create the ideal workspace, the one thing that many commentators seem to agree on is that a hybrid model is the way of the future. Let’s take a look at the top right corner of the matrices. From both willingness and ability to organisational and personal empowerment, we are headed toward giving the individual choice.

Figure 7 – Remote Work Willingness Matrix (Source: Chelsea Perino)

Figure 8 – Empowerment Matrix (Source: Chelsea Perino)

Figure 9 – Reimagine Work: Employee Survey Dec 202-Jan 2021 (Source: McKinsey & Company)

Workplace strategists are challenged with balancing the needs of employees (work-life balance, best ‘place’ for the task in hand, technology access, etc.) with the needs of their clients (brand/culture, operational resilience etc.), and overall business performance (profitability, cost efficiency/space use efficiency). But it seems that the COVID-19 pandemic has created some alignment between these potentially conflicting goals.

Remote work is here to stay

Forbes quoted the data scientists at Laddars’ projections which indicated that ‘25% of all professional jobs in North America will be remote by the end of 2022, and remote opportunities will continue to increase through 2023’. Remote working opportunities increased from under 4% pre-pandemic to about 9% at the end of 2020, and to more than 15% in the beginning of 2022 (12). At the same time, more than 24 million American workers quit their jobs between April and September 2021, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labour Statistics. Organisations are recognising that the providing workplace choice plays a role in combatting the ‘great resignation’. (13)

In The Executive Centre’s Business Sentiment Survey for H1-2021, 83% of respondents indicated that flexible workspaces were important to their business operations (16). Flexible offices are of course only one of the many different ‘third spaces’ that exist, but both flexible providers and the operators of alternative third spaces alike have started to rethink their products to better suit the mobile worker.

While we might not be clear on exactly what the workplace will look like in the future, one thing most commentators may agree on is that the importance being placed on trying to understand these dynamics, both on a personal and an organizational level, will have a positive impact on how and where we work tomorrow.

Understanding how places other than the corporate office or home (i.e., third places) fit into that ‘balancing process’ is essential in developing a workplace solution that is best for both the organisation and the people delivering the results. Companies already utilising flexible workspaces only see the importance of those third-place spaces increasing. W&P

Case Study: Standard Chartered Bank

Standard Chartered Bank is a leader in the adoption of flexible work policies, and they are striving to act as an example for other organisations trying to embrace new ways of working but are finding it challenging to create an architecture to empower change.

An internal survey indicated that that over 75% of their global workforce wanted a hybrid work model which typically consisted of 2-3 days at home and 2-3 days at the office or third space. While the bank had been working on workplace innovations pre-COVID-19, the pandemic served as a catalyst for them to develop a variety of different hybrid work options, as well as institute a multitude of work environments from which employees can choose to work (14).

In addition to their traditional leases, Standard Chartered Bank has also partnered with flexible office providers like The Executive Centre to provide their employees with more choice. Now, employees can work from home, work from SCB offices (both those traditionally leased and those within flexible providers) or choose from third spaces; the key is to empower employees and managers alike to think more strategically about how and where they work best, and for the organisation to provide the infrastructure for them to do so.

Shelley Boland, Head of Property Asia Pacific, Standard Chartered Bank said, “The talent of the future are expecting flex; whether that’s flexible work hours or locations. Successful adopters of flex will be those that have the foresight to model and visualise how workplace changes may affect business outcomes, processes, and employees, and be agile enough to constantly evolve their workspace to those needs. We see flexible office spaces playing a greater role in that strategy.” (15)

References

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescoachescouncil/2021/08/25/is-the-hybrid-work-model-worth-it-or-is-it-all-hype/?sh=6366c8d81f5a

- https://hbr.org/2020/11/our-work-from-anywhere-future

- https://www.adaptavist.com/

- https://www.businessinsider.com/working-remote-challenges-work-from-home-2019-10#its-easy-to-get-distracted-when-youre-working-from-home-and-you-may-not-be-as-productive-as-youd-be-in-a-traditional-work-setting-2 and https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200831005027/en/Stress-Burnout-and-Technical-Issues-Threaten-the-Benefits-of-Working-From-Home-According-to-Adaptavist-Study

- https://www.wtwco.com/en-US/Insights/2021/02/2021-emerging-from-the-pandemic-survey

- Organisational futureproofing in a post COVID-19 era. Perino.

- https://hbr.org/2021/01/work-life-balance-is-a-cycle-not-an-achievement

- Oldenburg, R., Brissett, D. The third place. Qual Sociol5, 265–284 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00986754

- https://www.hermanmiller.com/content/dam/hermanmiller/documents/white_papers/wp_the_future_of_work_looking_foward.pdf

- https://www.pwc.com/us/en/library/covid-19/us-remote-work-survey.html

- https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/what-employees-are-saying-about-the-future-of-remote-work

- https://www.theladders.com/press/25-of-all-professional-jobs-in-north-america-will-be-remote-by-end-of-next-year

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/bryanrobinson/2022/02/01/remote-work-is-here-to-stay-and-will-increase-into-2023-experts-say/?sh=6d6c202f20a6

- https://www.bloomberg.com/press-releases/2021-09-02/the-executive-centre-standard-chartered-on-future-workplace

- https://www.sc.com/en/global-careers/experienced-hire/working-here/flexible-working/

- https://whitepapers.executivecentre.com/form-1h21-tec-member-business-sentiment-report

About the Author

Chelsea Perino

With an undergraduate degree in Anthropology and Linguistics from NYU, a four-year solo trip around the world, and an MA in Public and Organizational Relations, Chelsea Perino worked in advertising both in New York and Seoul, South Korea. Chelsea is currently the Managing Director, Global Marketing & Communications at The Executive Centre (see below), whom she has helped establish as a leader in workspace experience, community, and corporate-culture facilitation.

Chelsea is passionate about organisational culture and believes that creating a dynamic and collaborative working experience positively affects team morale and productivity. She is an adjunct professor and published author, a regular guest speaker at corporate real estate (CRE) and marketing industry conferences, and a board member for several CRE organisations.

About The Executive Centre

The Executive Centre (TEC) is Asia’s premium flexible workspace provider, opened its doors in Hong Kong in 1994 and today boasts over 165+ centres in 33 cities and 14 markets. It is the third largest serviced office business in Asia.

The Executive Centre caters to ambitious professionals and industry leaders looking for more than just an office space – they are looking for a place for their organisation to thrive. TEC has cultivated an environment designed for success with a global network spanning Greater China, Southeast Asia, North Asia, India, Sri Lanka, the Middle East, and Australia, with sights to go further and grow faster. Each Executive Centre offers a prestigious address with the advanced infrastructure to pre-empt, meet, and exceed the needs of its members.

The Executive Centre empowers ambitious professionals and organisations to succeed. Privately owned and headquartered in Hong Kong, TEC provides first class Private and Shared Workspaces, Business Concierge Services, and Meeting & Conference facilities to suit any business’ needs.